Steven Pestana

Email: spestana@uw.edu

GitHub: spestana

Structure from Motion Survey of a River Channel

May 2018

River systems in the Pacific Northwest, like much of western North America, underwent drastic changes starting in the 19th century with the settlement of the region by European Americans. Including bank reinforcement, the cutback of riparian vegetation, removal of debris and dredging, and even re-routing river flows.

“For 500 generations they flourished until newcomers came… much was lost; much was devalued, but much was also hidden away in the hearts of the dispossessed…” Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest: An Introduction by David M. Buerge

Only much more recently have the calls for restoration and rehabilitation of the regions waterways been met with action, perhaps most notably with the Elwha River dam removals and ongoing river restoration in the Olympic Mountains.

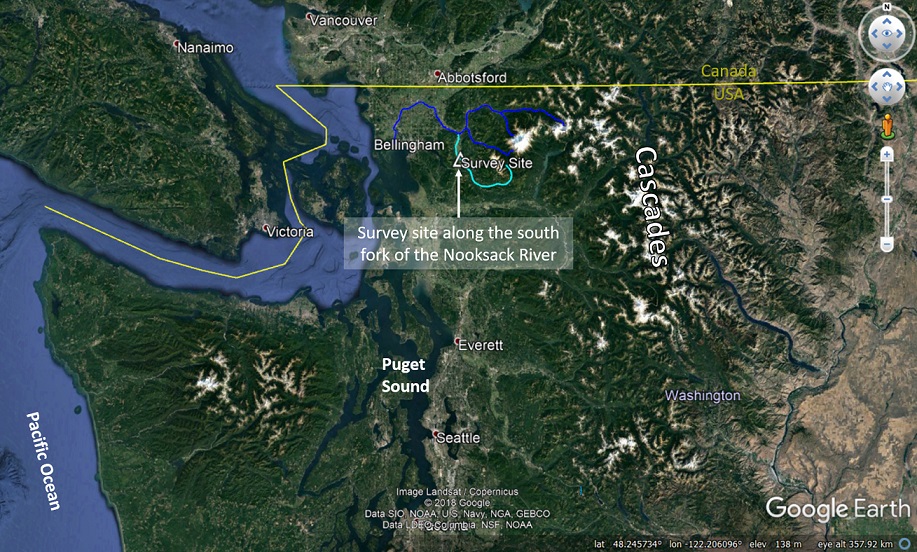

The Nooksack river drains the western slopes of the Cascade Range in northern Washington, including Kulshan, Mount Baker, an active stratovolcano. Its south fork meanders through a valley gridded by agricultural fields before the confluence with the main stem of the river near the Nooksack Indian Reservation.

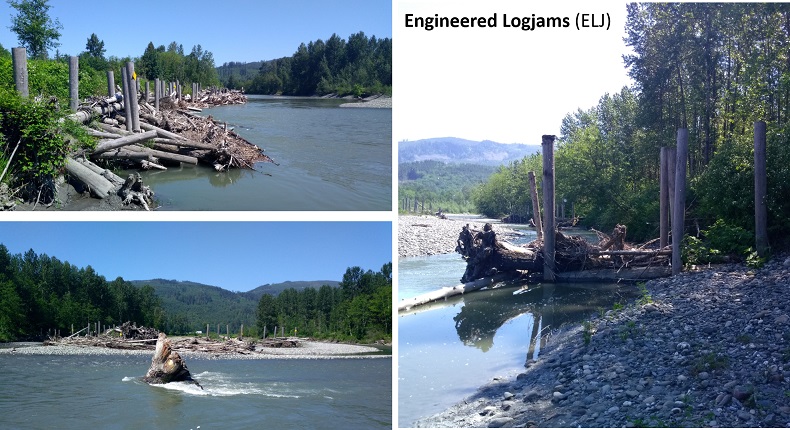

The south fork’s meanders have become relatively fixed between farm plots, held in place by bank reinforcement that in turn can increase flow velocities. The clearing of vegetation from its banks as well as its own tributaries in the logged foothills have also limited the amount of “woody debris” that the river carries downstream. These two factors (among many others) are detrimental to the local salmon population that return to the river from the Pacific Ocean to spawn. Low flow velocities through the meanders allow the fish to make their way further upstream against the current. Woody debris within the stream channel can slow flow velocities so that sand and gravel become deposited on the riverbed, creating braided channels and salmon spawning habitat.

A project to re-introduce the function of woody debris and gravel bars has been enacted on the south fork of the Nooksack river. These “engineered logjams” (ELJs) consist of tree trunks driven into the soil and tied together within the river channel. It is hoped that these will help catch what natural woody debris comes down the stream, and germinate the structures required to slow flow velocity and form gravel and sand bars.

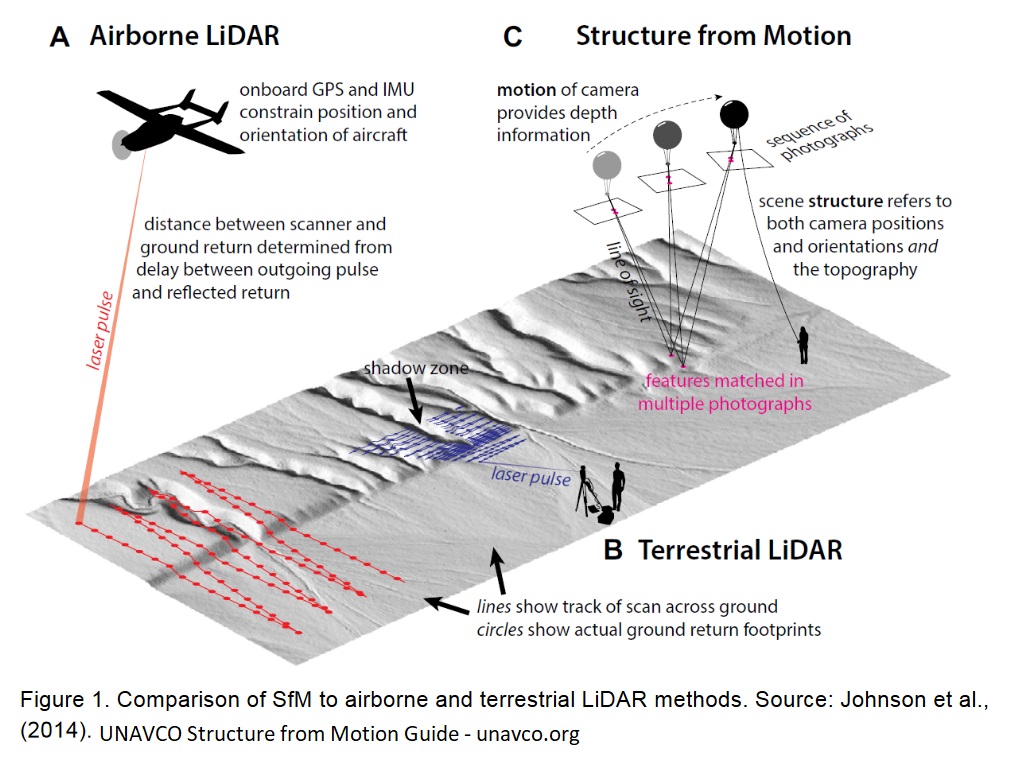

To assess the performance of the ELJs, surveys were performed to map the shape of the river bed. Lidar surveys (light detection and ranging) from a prior year could be compared against a new survey to determine how the land surface may have changed with the introduction of these structures . Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP) provided bathymetric measurements below the current water level, but instead of using lidar again to map the above-water river bed surfaces (at low flows, much of the river channel is exposed above water), structure from motion (SfM) using images from a small drone were used.

Lidar surveys are typically conducted from a single (or series of) fixed locaitons with a tripod-mounted “terrestrial lidar system” (TLS, as opposed to an airborne or spaceborne lidar system). To conduct a survey of the ELJ study site along the Nooksack, multiple TLS scan positions would be needed to provide views of all the river bed surfaces of interest, which takes a lot of time and effort to relocate and set up equipment multiple times. Using a small drone to capture aerial images for a SfM survey allows us to survey a similarly sized area from a single launch/landing position.

Structure from motion methods are a leap forward from traditional stereo photogrammetry which had previously supplied the data for creating topographic maps across the United States. Unlike stereo photogrammetry which provides two images analogous to perceiving depth by viewing a scene with two eyes, structure from motion can utilize 100s and 1000s of “eyes” to view an object or scene from all angles.

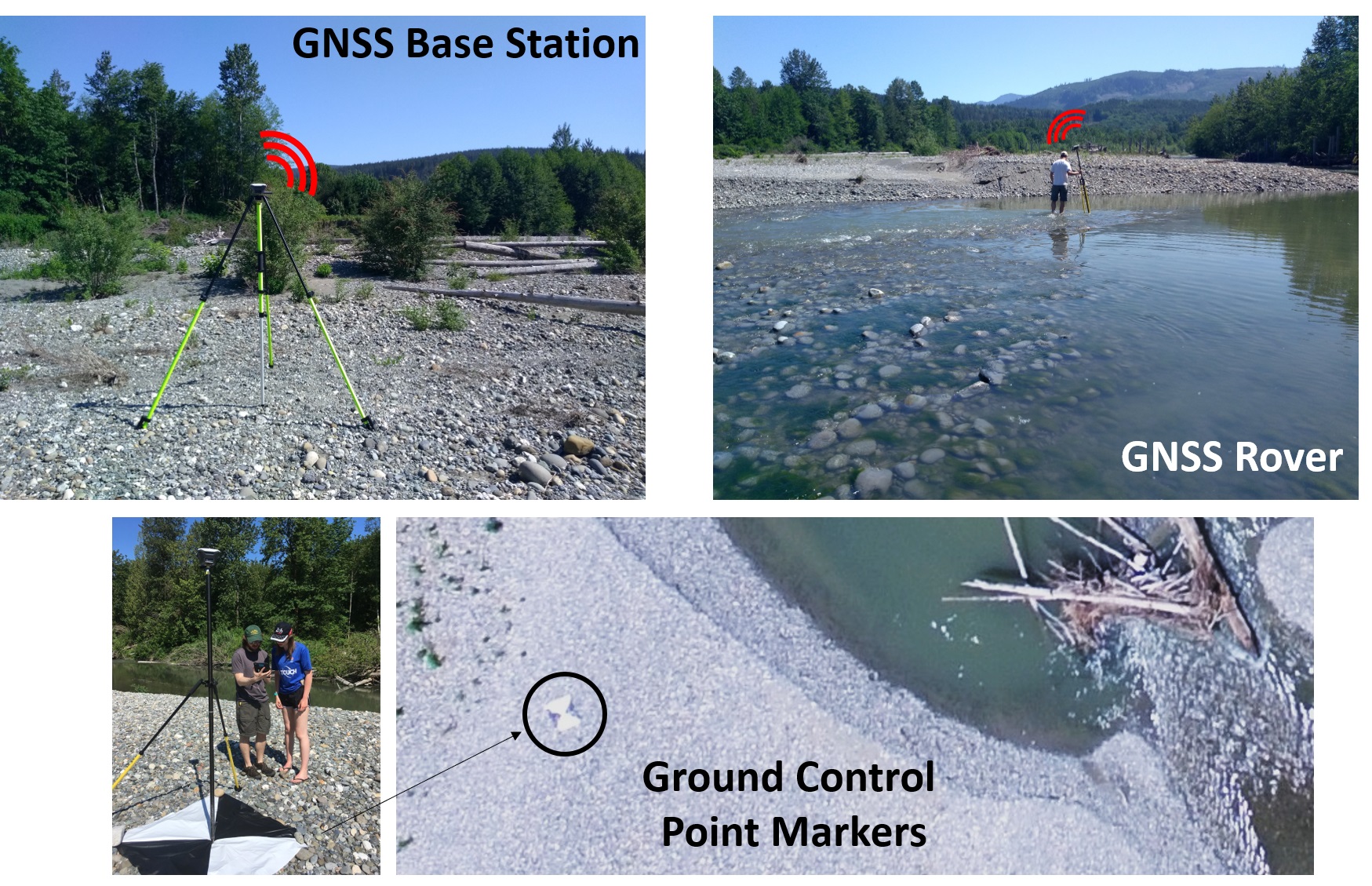

Before the drone could be launched to capture its images across the survey site, ground control points needed to be placed and their locations logged using high-precision GNSS (Global Navigation Satellite Systems, the generic term for constellations of navigational satellites, which includes the American GPS system among others). A GNSS base station was first set up to provide a long-term log of geolocation information at a fixed central location for the duration of the survey. This allows high accuracy to be established on a fixed site. The base station communicates error correction information to a “rover” GNSS unit that is taken to each ground control point to log its position. High-contrast black and white tarps served as ground control point targets since these are easily visible in the imagery taken high above the ground.

Following the logging of all ground control point locations, the drone could finally be launched to perform its survey. Multiple flights (using up all the batteries brought along in the field) helped cover different reaches of the site at a range of altitudes (which will translate to a range of image resolutions) and view angles.

Processing the resulting imagery (which itself has some geolocation information from the drone’s GNSS) together with the ground control point locations provides a digital elevation model (DEM) over which the visible imagery can be draped, creating an orthorectified image mosaic. The resulting DEM can now be used to compare against previous surveys to look for changes in the topography, perhaps due to the influence that the ELJs have on the river’s flow.

Thanks to the folks who invited me out to help with this project!

Seen from the drone’s point of view: Annie Ockelford and her student Chloe, Joanna Curran, Jacob Morgan, and myself.

- Writing an Inclusion Plan for NASA proposals

- Warming (climate) stripes in python with ulmo

- Teaching Data Analysis in Water Science (Fall 2020)

- American Geophysical Union 2019 Fall Meeting

- Structure from Motion Drone Survey of Easton Glacier

- Structure from Motion Survey of a River Channel